Radon is Under the Radar for Many Missouri Homeowners

Lynette Waltersdorf hadn't given much thought to radon until a few weeks ago when she and her husband bought a home and tested for the invisible, odorless gas.

Several days later, she found herself watching John Frierdich of St. Louis Radon drill a 4-inch wide hole into the concrete floor of her basement to install a mitigation system.

Turns out, radon levels in the newly built home, in O'Fallon, Mo., were more than twice the safe level.

The Environmental Protection Agency recommends levels below 4 picocuries per liter of air. The Waltersdorfs' was 10.

"Our Realtor told us to have it tested," said Waltersdorf. "She said just to be safe, we should have it done."

The Waltersdorfs were fortunate their agent suggested the test. By law, Realtors in Missouri are not required to mention radon. It's listed on the seller's disclosure statement along with mold, lead, asbestos and methamphetamine production, where it can easily be missed because many sellers check a box stating they're unaware if the home has been tested or treated for radon.

In Illinois, several pieces of legislation, including the Radon Awareness Act of 2008, have been passed thanks, in part, to Gloria Linnertz of Waterloo.

After her husband died of lung cancer, she found out that the home they'd been living in for 18 years had more than four times the maximum safe level of radon.

Now, the Radon Awareness Act requires Illinois home sellers to provide a separate, more detailed disclosure form and educational material on radon to home buyers when the contract is signed.

It's a simple, low-cost piece of legislation that helped boost testing in homes that are sold each year from 8 percent to more than 35 percent, according to state radon officials.

Linnertz also worked with legislators in Missouri for two years trying to get similar legislation passed without success.

"Part of it is because they're not educated about the danger of it," she says. "I had sent some of the legislators information to explain what it was, but not to the extent as I did in Illinois."

RADON AND CANCER

Radon is an invisible, odorless radioactive gas that occurs naturally when uranium and thorium decay in the soil. It's in the atmosphere around us, but at safe levels typically well below 1 picocurie per liter. It's a known carcinogen in high doses, and the EPA estimates that it kills 21,000 people each year.

Scientists made the link between radon and lung cancer during the 1950s in the Czech Republic, when they realized that non-smoking uranium miners ran an unusually high risk of getting lung cancer. Studies since then confirmed that high levels of radon in residences also pose a risk.

One of them, which was published in the science journal Epidemiology in 2005, analyzed data from seven large scale case-control studies in North America that included 4,081 people with lung cancer and 5,281 people who did not have lung cancer.

The scientists measured the levels of radon in residences occupied within the five to 30 years before diagnosis or acceptance as a control. Based on those results, they estimated that residential radon causes between 10 and 15 percent of all lung cancer deaths in the United States each year, making it the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, and the No. 1 cause among nonsmokers who die of lung cancer.

A similar European study published in the 2005 British Medical Journal came to the same conclusion. It measured and analyzed radon levels in the homes of 7,148 people with lung cancer and 14,208 without lung cancer.

Linnertz was shocked when her husband, Joe, a nonsmoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2005.

She remembers the oncologist mentioning something about radon, but her husband's health was declining so quickly that she didn't have time to think about it. He died a few weeks later.

About a month after he died, Linnertz heard radon mentioned on NBC's "Today." She looked it up on the Internet and bought a home test kit.

When the results came back and she saw that her level was 17.4 picocuries per liter, she hired a mitigator to install a system. Then she threw herself into researching radon. She didn't want the death of her husband to be for nothing.

"We were both retired and we had no children. We took care of each other," Linnertz says, her voice shaking with grief. "When he died, I prayed to God to give me a reason to live. When I found out that radon more than likely contributed to his death, I struggled for a while but knew I had to get a law passed so people wouldn't buy homes with high levels of it."

MITIGATING THE PROBLEM

Mitigation, which includes testing, installing a system and then retesting, typically runs $700 to $1,200.

At the Waltersdorf home, St. Louis Radon drilled the 4-inch wide hole through the concrete floor and into the soil below. They excavated between three and five gallons of soil, and installed a PVC pipe that ran from the hole beneath the foundation, up the wall of the basement, then the interior wall of the garage and on through the ceiling and roof. Then the company sealed the hole shut around the pipe so it was airtight, installed a fan that created a vacuum effect to suck the radon up and into the outdoor air where it could dissipate.

A gauge in the garage will allow the Waltersdorfs to monitor the vacuum's force and alert them when the fan needs to be replaced.

Tom Getchman, owner of St. Louis Radon, expects the mitigation system will push the radon level in the Waltersdorf home below 2 picocuries per liter pretty easily, because it's a new home. He suggested they test for radon every two years.

Getchman says he gets calls from all over the area.

"You can't look at one house and say, 'This house has it and the next one does too,'" he says. "The one next door could be perfectly fine. I've done testing on condos on the same slab and one on one side will have it and the other will not."

The EPA has maps that are zoned according to radon exposure risk. But Patrick Daniels, radon program manager for Illinois, said they can offer a false sense of security and misinform inexperienced real estate agents, who could tell people they don't need to test because they are buying in a low-risk zone.

"The problem with mapping is, people say, oh, we're a moderate potential. But that means 25 to 50 percent of homes will fail a radon test," he said. "The message for our state program is that the only way to know is if you test. Even in our most southern regions, which are zoned lower risk, we've had homes test with 40 pci."

When Linnertz, a retired elementary school teacher, decided to do something about protecting others from the invisible, odorless gas, she researched it tirelessly. Then she persuaded Rep. Daniel Reitz, D-Sparta, to help her craft the awareness act and sponsor it. She spent the better part of the year after that educating Illinois legislators about radon.

When it came up for vote, it passed unanimously in both chambers.

But Linnertz didn't stop there.

Last year, she worked with the American Lung Association and the American Association of Radon Scientists and Technologists to get legislation passed in Illinois that all day care centers, including home day cares, must be tested for radon every three years and fixed if they have a radon level of 4 picocuries per liter or more. Starting next year, another bill that she advocated for would require all new homes be built as radon resistant.

"I've pushed it in Missouri, but they haven't done anything," she says. "They don't even have a law that says that radon professionals have to be certified or licensed. Anyone who wants to can go out and say I can fix your house for radon."

Illinois requires radon mitigators to be licensed by the Illinois Emergency Management Agency and to report all systems that they've installed to the state. Fourteen other states also require mitigators to be licensed or certified.

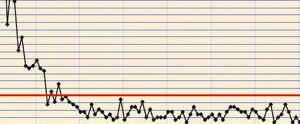

Since the Awareness Act was enacted, the number of mitigations in Illinois has increased dramatically.

In 2007, 5,628 mitigation systems were installed, says Daniels. That number jumped to 6,839 in 2008. Last year, 9,902 were installed.

Meanwhile, Randall Maley, a radon official with the Missouri Department of Health, estimates that 2,300 mitigation systems were installed in Missouri in 2011, though there's no specific number because radon specialists are also not required to report the systems they install.

Trudy Smith, senior training specialist for Spruce Environmental Technologies in Massachusetts, a company that offers equipment and services to the radon industry, says the quality of testing and mitigation is much better in states that require licensing.

Linnertz is ready to continue her efforts in Missouri.

In the meantime, she'd like to make the Radon Awareness Act a federal law and see the EPA lower the safe level of radon from 4 picocuries per liter to 3. The World Health Organization has set its safe level at 2.7, she notes.

She now sits on the board of directors of the American Association of Radon Scientists and Technologists and will travel to Washington in coming weeks to attend the group's board meeting. She hopes to also meet with members of Congress.

"If I'm speaking to any of them, I'll tell them about the Radon Awareness Act and that it has made a big difference and that it'd be great for a federal law," she says. "Lives can be saved in every state."